The British and other Western colonial powers often used ‘great exhibitions’ to showcase the ‘splendours’ of their colonies as they saw them—strange and exotic. But, as we find, in the famous Jaipur Exhibition of 1883—under the patronage of Maharaja Madho Singh II—the nature of exhibition transformed into a showcase of local industry and craft culture as Indian nobility would like it to be seen, thus setting the tone for the future of Indian museology. (In pic: A painting depicting the India pavilion at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London by Joseph Nash; Photo courtesy: Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021)

Of all of the exhibitions of Indian arts and exotic wonders held during the colonial period, the Jaipur Exhibition of 1883 is perhaps the most significant. Within the history of Indian museology, it was the first time the ‘Oriental gaze’ was lifted, and Indians presented themselves and their treasures to the world as they wanted it to be seen, rather than through the eyes of the British. With maharajas and noble families from the region providing their most interesting treasures for display, it was quite a spectacle.

When they began, exhibitions were a way for the East India Company and colonial state to boost the Empire both economically and in popularity. The first one, the Great Exhibition of 1851, was held in Alexandra Palace in London, with an ‘India Exhibit’ that saw everything from jewels to a stuffed elephant shipped to Britain for public viewing. Some exhibits even displayed colonised people in ‘human zoos’, portrayed as strange, different and exotic. Curated by the British and built to benefit the Empire, they only represented colonised cultures from an outsider’s point of view. Nevertheless, they were popular, and other European colonisers followed suit.

This is where the Jaipur Exhibition was different. It was a product of the passion for local arts of two successive Jaipur maharajas—Sawai Ram Singh II and Sawai Madho Singh II. The former built up Jaipur as a centre of the arts, setting up the famous Jaipur art karkhanas (workshops), and the latter continued his work, putting it on display at the exhibition for the world to admire. Parts of the exhibition are still visible today, after Madho Singh II housed them as a permanent museum at the Albert Hall, Jaipur.

Fig. 1. Pages 8 and 9 of Memorials of the Jeypore Exhibition, 1883, by Thomas H. Hendley, 4 Vols, Industrial Art (Courtesy: HathiTrust)

An Indian and an Englishman

Ram Singh II had proposed an industrial arts museum in Jaipur, but the project was stalled after his death in 1880. However, his successor Madho Singh II—along with an Englishman Thomas Holbein Hendley— soon revived it. Technically Jaipur’s Chief Residency Surgeon, Hendley’s interest in Indian arts saw him involved in large-scale projects despite little formal arts training. In 1881, months after the approval from the durbar for an exhibition, an acquisition of the finest examples of regional arts industry began.

A few Indians were specifically appointed to make the purchases as prices would quickly double if Hendley himself ventured into markets. One such person was head clerk Pandit Braj Ballabh, whose curation of objects for the exhibition represents the beginnings of an Indian museology practice by an Indian. Highlighting the contributions of Ballabh and his Indian colleagues, historian Giles Tillotson argues the maximising of both commercial productivity and public interest in Jaipur’s arts industry. The curated objects, initially stored in a small building, garnered huge interest with over three thousand visitors a week, the vast majority of which were Indian. This success spurred the creation of the exhibition that opened in January 1883.

Fig. 2. The Prince Albert Hall in Jaipur, where the 1883 exhibits found a permanent home (Courtesy: HathiTrust)

Cultural Splendour

Launched in a large hall attached to the Jaipur City Palace, the final exhibition contained hundreds of examples of embroidery, pottery, textiles, stone and wood carving, and various forms of metalwork, including koft gari (gold inlaid on steel). As Hendley writes in his Memorials of the Jeypore Exhibition, 1883, objects were loaned or given by the Viceroy, 25 princes and nobles or other wealthy individuals. Eight Indian and five British jurors gave gold, silver and bronze medals, and special certificates awarding the best craftsmanship.

The most valuable objects were kept in the Great Hall. This included rich brocades and embroidered textiles hung on purpose-built wooden towers, and magnificent old and jail factory carpets and paintings. The most popular items were diamonds, loaned by the Maharaja of Punnah, and crowns and jewellery pieces sent by the Maharaja of Alwar. All of this symbolised not only the Indian subcontinent’s monetary grandeur but also their cultural worth.

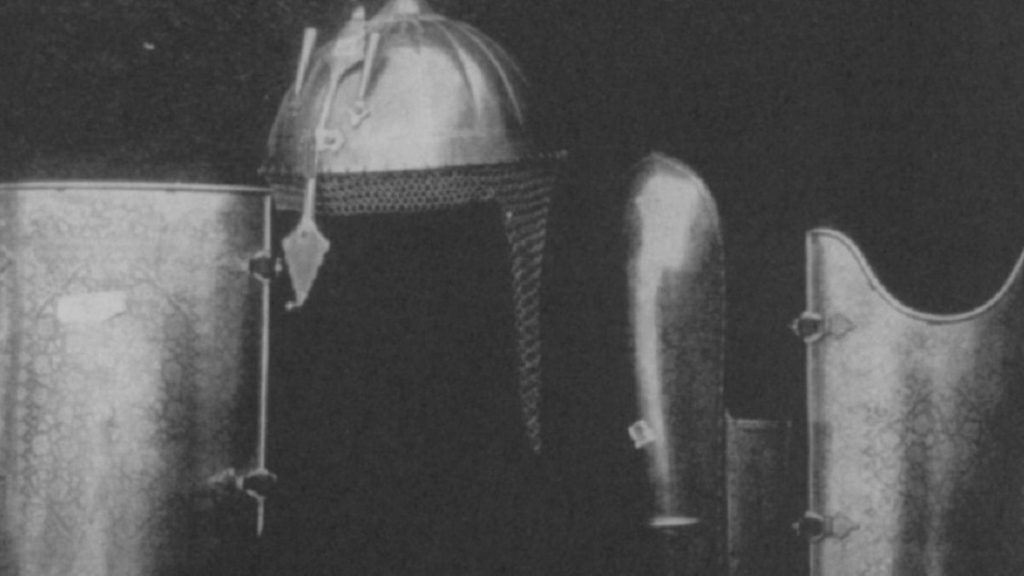

Praise was heaped on the exhibition, with Rudyard Kipling, then principal of the Lahore Government School of Art, remarking that ‘it was doubtful whether a more choice or interesting collection of Indian arms had ever been assembled in India.’ Beyond winning an award, and a small cash prize, certain objects were featured in Hendley’s Memorial Volumes. These were sent across Europe to the most important museums and libraries of the day to showcase the exhibition’s splendour.

Fig. 3. Armour with koft gari by Fateh Din of Sialkot, gold medal winner. From Thomas H. Hendley's Memorials to the Jeypore Exhibition, Vol. 2 (Courtesy: HathiTrust)

Fig. 4. South Kensington cases used in the Jeypore Exhibition 1883, as documented in Thomas H. Hendley's Memorials to the Jeypore Exhibition, Vol. 4 (Courtesy: HathiTrust)

Finance and the Future

The exhibition could have also helped Jaipur’s industrial arts industry by encouraging European clientele to purchase similar objects. Like the international expos of the 1970s and 1980s, and the India International Trade Fair today, Hendley’s volumes—with detailed listings—functioned like a price list for potential buyers. As historian Claire Wintle has argued, the continuity in international exhibitions for former colonies post-Independence highlight that visual culture was a way for these new nations to decolonise, and to present themselves to the world on their own terms, a process seemingly already under way in Rajasthan in 1883.

In 1887, the exhibition was reinstalled in the newly built Prince Albert Hall, named after Prince Albert’s 1876 visit to Jaipur. Quite uniquely, people were allowed to borrow pieces to study and replicate, demonstrating the museum’s role as a resource for local craftmanship and not only as a tourist destination for colonial travellers. The ‘South Kensington Cases’ used in the exhibition (and still there today) were copies of those at London’s present-day Victoria and Albert Museum, and were considered to be at the forefront of museology practice.

Throughout Hendley’s volumes, the 1854-founded South Kensington Museum is referenced, indicating that the Jaipur Exhibition of 1883 was considered to be at par with London museums.

However, the most remarkable thing about the exhibition is not the connection with Britain, but the way in which the Jaipur durbar managed to create space to showcase industrial arts and craft traditions as they wished them to be seen, marking the beginnings of Indian museology. Unlike others, like the 1851 Great Exhibition, which relied on typical tropes and had ethnographic displays like ‘groups of figures illustrative of Indian manners’ which no doubt presented caricatures, the 1883 exhibition was drawn from rich crafts traditions and designed to illustrate them.

With the maharaja as patron, it was as much a commercial success as British versions, with nearly a quarter of a million people attending. It also convinced the colonial government of Jaipur’s potential. Following this, the maharaja was invited to create the ‘Rajputana’ exhibits for the Indo-Colonial Exhibition of 1886 in London. This, as historian Giles Tillotson highlights, meant that Jaipur had successfully established itself as a centre for Indian and regional arts and crafts, and the Prince Albert Museum is a permanent legacy of this process.